The limits of torque compensation.

Jan 24, 2026

In any internal combustion engine, power is the product of how much “push” you have (torque) and how fast you apply it (RPM).

Power = Torque × RPM

At first glance, it seems logical that spinning an engine faster will always produce more power. However, every engine has a physical ceiling—a point where torque drops so rapidly that increasing RPM can no longer compensate.

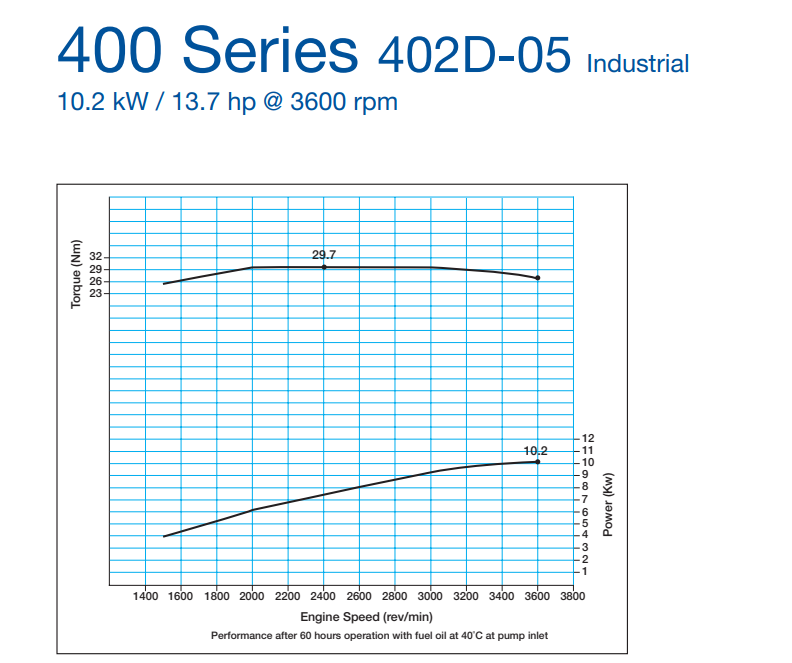

Example: Perkins 400 Series – 402D-05 Industrial Engine

The torque and power chart of this engine clearly shows three distinct operating phases.

Phase 1: Torque Climb (1,500 – 2,400 rpm)

In this early stage, the engine is building its strength. Torque rises from roughly 25 Nm at 1,500 rpm to a peak of 29.7 Nm at 2,400 rpm.

What’s happening in this phase:

As the engine speeds up, volumetric efficiency improves. More air and fuel enter the cylinders effectively, creating a stronger combustion push on the pistons. Because both torque (strength) and RPM (speed) are increasing at the same time, power rises steadily.

Phase 2: Peak / Plateau (2,400 – 3,000 rpm)

This is the engine’s sweet spot for high-efficiency operation.

Torque reaches its maximum value of 29.7 Nm at 2,400 rpm and remains almost perfectly flat up to 3,000 rpm.

Even though the engine is spinning faster, torque does not drop yet. Since power equals torque multiplied by angular velocity, the flat torque curve allows the power curve to continue climbing in a stable, nearly linear manner. This range is ideal for continuous and heavy industrial work.

Phase 3: Power Drop-Off Transition (3,000 – 3,600+ rpm)

Beyond 3,000 rpm, torque begins to decline, dropping toward about 27 Nm. At this point, increasing speed can no longer compensate for the loss of torque.

This happens for several reasons:

At very high RPM, the intake valves open and close so quickly that there is not enough time for the cylinder to fill completely with air. Diesel combustion also requires a finite amount of time to ignite and burn; at extreme RPM, the piston may be moving downward faster than the expanding gases can effectively push it. If combustion is not completed before the exhaust valve opens, part of the energy is lost through the exhaust instead of being converted into useful work. Additionally, mechanical friction between pistons, bearings, and the crankshaft increases exponentially, consuming a significant portion of the engine’s own generated power.

When the engine hits 10.2 kW at 3,600 rpm, it has reached its mechanical limit, beyond this point, the torque can no longer compensate for the high speed, leading to an inevitable drop in total power.